The Toronto and San Francisco Mozilla offices each feature very different coffee makers.

The Toronto office has a Rancilio Epoca espresso machine. It has lots of knobs and switches, and one has to be taught how to use it. When one learns, the first few drinks they make are likely to taste very bad; a conscious effort must be made to learn from one’s mistakes and create better drinks.

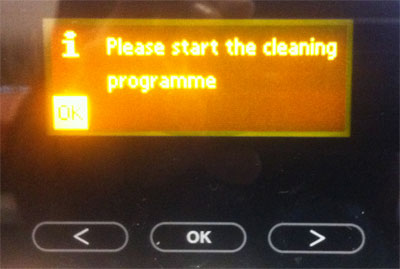

The SF office has a Miele espresso machine with three buttons and an LCD display. It’s comparatively easy to use, and makes fine drinks at the push of a button—until something goes wrong in the opaque innards of the machine. The sight of error dialogs like this one are extraordinarily common:

The machine probably has as many different kinds of error messages as a modern computer operating system. Like an operating system, it also offers little to no assistance on how to fix the problem that’s occurring.

Both of these coffee machines reflect very different philosophies about the nature of tools, and about the people who use them. For me, one of the most interesting aspects concerns the communities that have grown—or failed to grow—around them.

Actually, the very existence of the Toronto office’s espresso machine is due to community: as I understand it, a core group of Torontonian espresso aficionados decided to buy a small communal machine with their own money, and upgraded the machine later on. The result I’ve noticed, whenever I’ve visited the Toronto office, is that the kitchen area becomes a place for learning. People are constantly teaching each other how to make a better drink, asking questions, debating the proper pressure to use when tamping (“approximately the weight of a cat”, says one coworker), and so forth. In a growing workplace that is constantly in danger of being segregated by organizational boundaries, a community of practice that’s centered around something completely unrelated to work is an amazing asset.

In contrast, there isn’t much of a community that can form around the push-button Miele machine in the San Francisco office. Because there’s no way to go “under the hood” and customize one’s coffee-making experience in a positive way, there’s not really any technique to share with others. An interface that is so “self-serve” and “easy to use” that it prohibits nuance and customization is also one that doesn’t encourage people to talk about it.

This might be an acceptable trade-off, except for the fact that the Miele isn’t fully self-serve. Like any machine, it needs maintenance, and because there was never an incentive for anyone to understand how it worked, very few people know how to fix it—if anything, I’ve experienced a sense of resentment when I’m presented with an error, as though the machine has violated its contract of being mind-numbingly easy to use. Consequently, the only talk I’ve ever heard about this machine revolves around its inscrutable error messages, which only the office manager knows how to fix.

The same dynamics I’ve described here apply to all of our tools. No matter how easy and “self-serve” we try to make our software, a significant portion of its users will still run into problems and use cases that they don’t know how to get past on their own. I don’t know if it’s possible to foster communities of practice through tools designed for freedom and empowerment—even if we put the Rancilio in the San Francisco office, for instance, it may languish if no one there thinks a good espresso is worth learning how to make. But it’s certainly worth finding out.